looking for the book with the pages torn out

🔖 feb. 8, 2025 - sat 11:30 pm

mood: antsy

music: bathroom sink

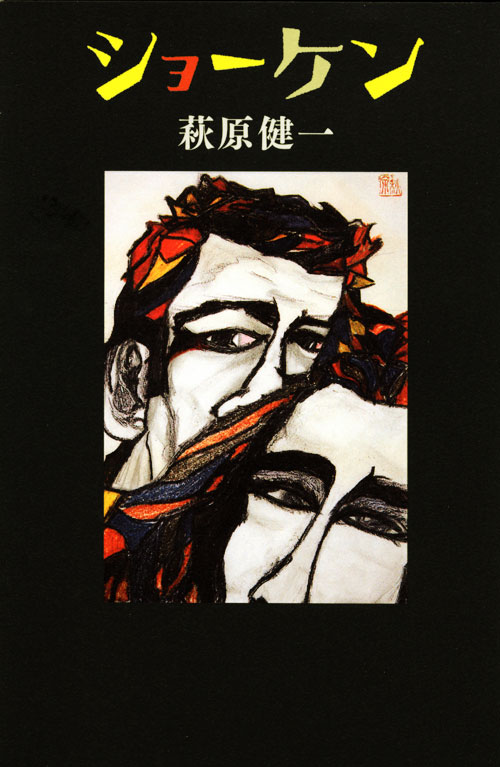

I started reading Hagiwara Kenichi's autobiography that I got in the mail a couple days ago and I am now thinking about this painting:

It was only recently that I found out from some old article that he had been a talented painter since he was quite young. He made it into a national exhibition in elementary school? Or prefecture-wide? Something like that, I'm sure. There was a reference to a habit he had of staring at people whose faces interested him, thinking about how to draw them. (I've been wanting to make a GS page on here just to house some of these bits and pieces I've come across, but I haven't gotten around to it...)

I was dying to know what his art had looked like, and then some days on from this curiosity, when I turned the opening pages of his memoir, I saw it — his name was listed under the credits for the cover illustration.

So Schiele!

Maybe I'm conflating two problematic faves reaching, but there's something of old Egon in Shoken to me. Tormented, provocative, offensive to public morals. When I think about it, Modorigawa (1984), with all its pathetic sex and death and clumsy overtures toward art, vaguely reminded me of watching his biopic, I guess. (The newer one from the last decade, not the one with Jane Birkin and the Brian Eno soundtrack. Although that one was fabulous and I've been meaning to get my hands on the Japanese DVD release of it for years now.) Shoken thought he was going to Cannes with that movie; his drug arrest put a quiet end to that notion, probably for the best of all involved.

Still, Ninagawa Yuki said something about him in that film that I can't quite remember now but that stuck in my mind as true anyway, that he embodied not decadence but raw will, the dirt accumulated under the fingernails of a person fighting to live. I can't explain what about this attracts me so much. There was a quote from 1982, around the peak of his addiction, in response to the question of whether or not he liked who he was: "If I didn't, I would've already killed myself." In the years since my mind finally cleared, I realized I must have wanted to live all along to have gotten this far, to have endured everything I have. I thought about that reading the beginning of his book — his refusal to die, his desperation to make it out the other side, clawing his way up from hell.

Schiele's mother-and-child pictures all evoke a sort of toxic enmeshment in my eyes, cadavers suffocating the life out of offspring who appear somehow flagrantly, impermissibly separate, too weak to extricate themselves from the rot but all too aware of every shallow breath being sucked from their powerless lungs. In the 2000s, when he was sober, I read that Hagiwara had privately painted a series of works around childbirth, questioning the concept of life and nature. His mother was some twenty years dead by this point, having passed away the morning of his court hearing in 1984. It was believed to be suicide. In his memoir, he said that his mother had considered aborting him, who alone had a different father from his four older siblings, unbeknownst to him until her death. A fortuneteller told her that Hagiwara would be a tremendously difficult child. "But my mother gave birth to me," he wrote. "And in the end, that prediction was right."

"54 Days, Waiting in Vain," a song about his time in prison on drug charges, performed at his 1985 comeback concert.